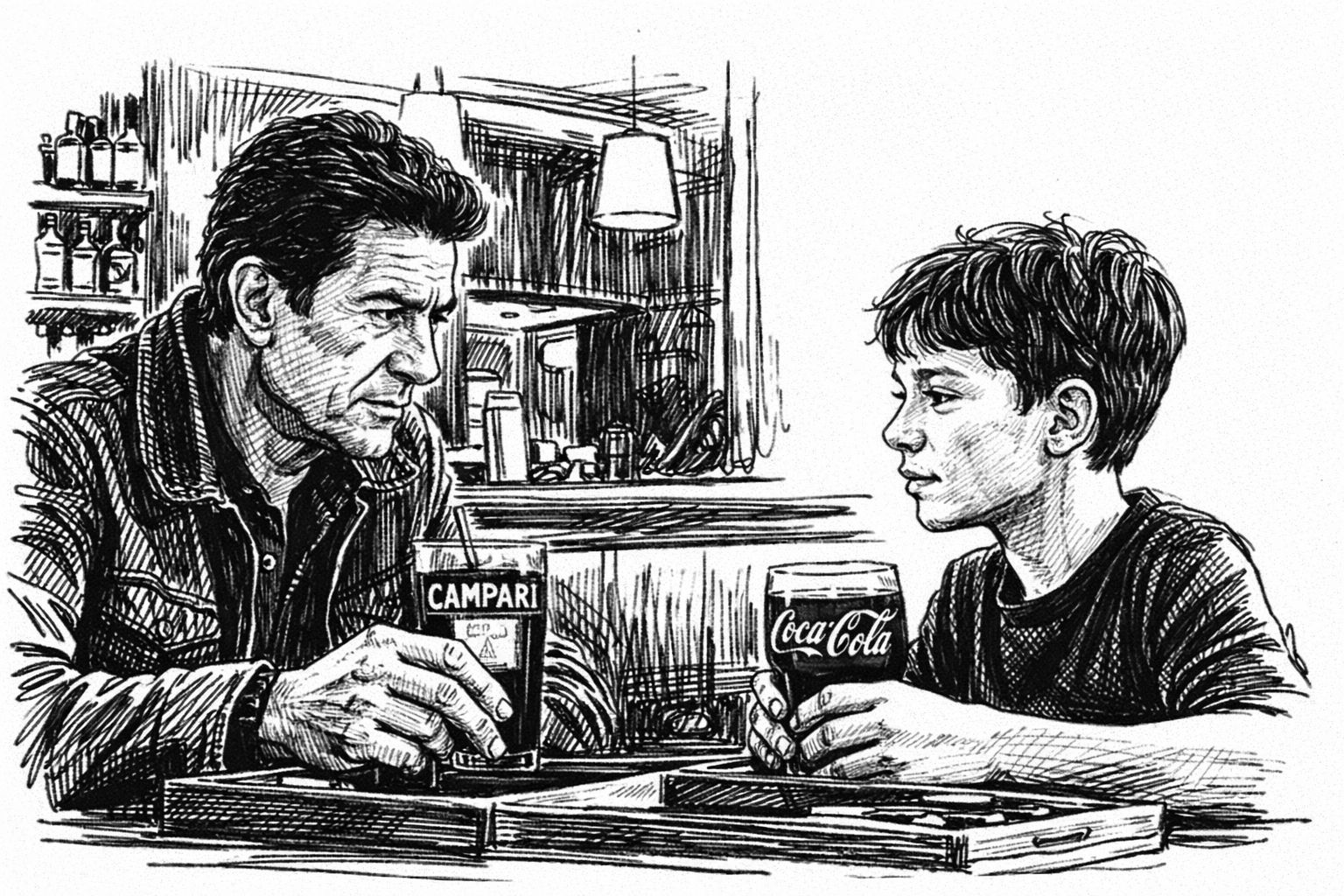

Uncle Patrick

In the bruised cathedral of the dive, where saints of neon bleed slow crimson on the walls, I sit beside the ghost of Uncle Patrick—silent, eternal—his Campari glowing like a ruby heart torn fresh from some old wound. The smoke hangs in veils, a funeral lace for dead afternoons, and the glass trembles between his absent fingers, whispering of Johannesburg rains and women who vanished like notes from a cracked piano.

Saturday was our pilgrimage then: child-me with Coca-Cola fizzing hymns on my tongue, him baptizing sorrow in red liquor while the turntable wept Sinatra through cigarette scars, warped and holy. Floors glued with yesterday’s confessions, tables scarred by knives of the broken, cheap wine flowing the way grace used to—thin, bitter, necessary. The jukebox coughed up the blues like a dying man coughing up blood, and we knelt there, faithful in the stink of it.

Now the vinyl is exiled, the needle crucified, and cold compact discs spin lies in coloured light. Yet I order the forbidden Campari anyway, taste the iron of memory, feel the cold day claw the windows like a lover who won’t be refused.

Uncle Patrick leans close without leaning, breath of absence on my neck, and the room tilts, the same old tilt—life still in disorder, still spinning, still singing its cracked, endless, beautiful lament. I raise the glass to the empty stool—your move, old man, it always was.

playing backgammon,

his passing not forgotten,

sitting in his chair.