The Honey Jar

and so the boy tormented them day after day, those natives on the hot African farm, pushing them until they wouldn’t even bring his tea and biscuits anymore, hands trembling at the thought of him, that pale cruel child with his secret games.

sometimes he’d palm it quick under his hand or slide it up his sleeve where it tickled and crawled against his skin, alive and secret, a living thing that made him smile inside with dark joy.

other times he’d drop it into the empty teapot, waiting for the kitchen staff to lift the lid—those jumpy souls already fearing what might leap out—an ambush from nowhere, and then the screams ripping through the air, the panic exploding, women fainting dead away on the stone floor.

the house-boy, that quiet man from Mozambique with sad eyes, would come in after and calm them down, murmuring promises that he’d speak to the cruel little boy, set him straight, but he never did, no, fear held him back, fear of another sharp telling-off from the white child’s father.

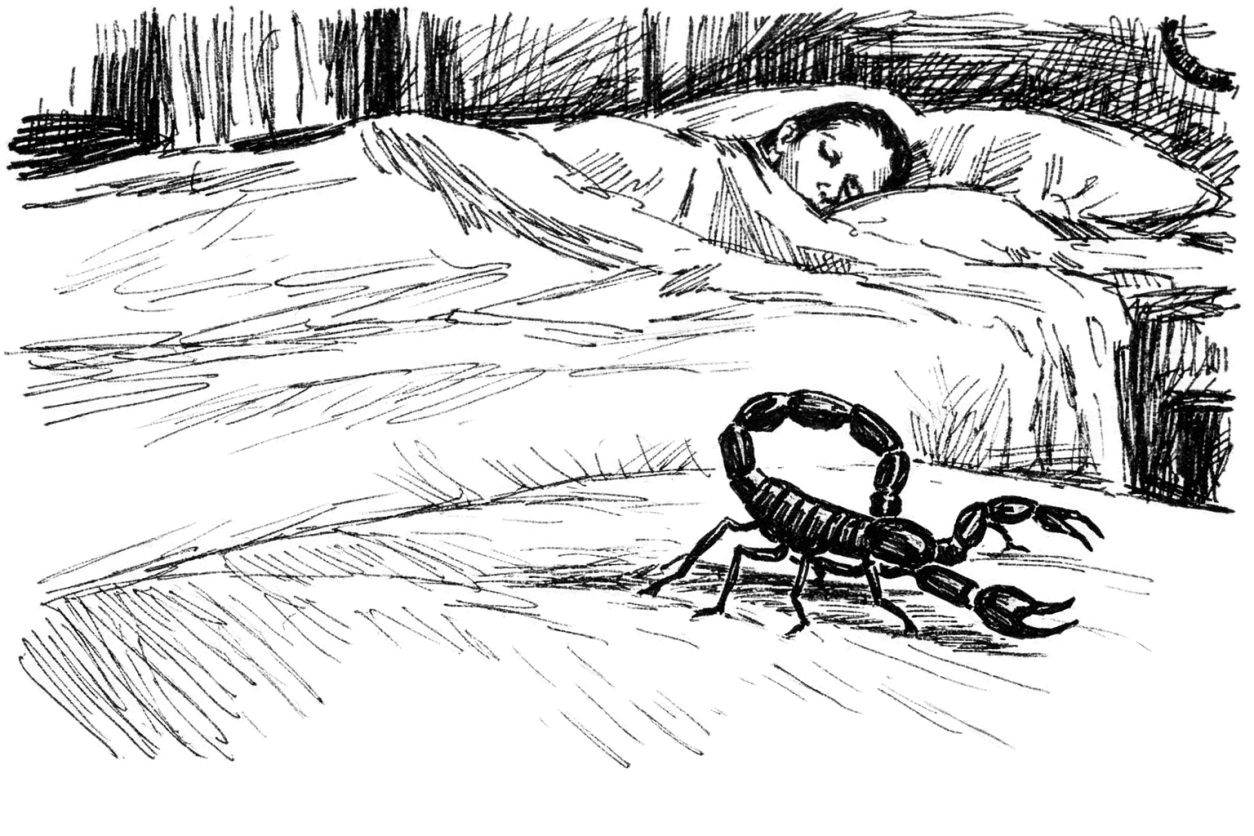

he kept it in a jar on his table, an old honey jar with a yellow lid punched full of little holes, air holes for breathing, and he lined it with sticks and dry hay. from there, it had a full round view of the world through the sunny window, everything spinning 360 degrees in the heat.

he’d tap the glass now and then, gentle taps, just to see if his little friend still moved inside, still lived. and he fed it once a week, a big African locust with legs like razors and wings green and grey, dropping it in alive. and he’d taunt it too, starve it sometimes until it grew vicious, ferocious, banging against the glass in rage. nights, he’d sit there in the dim room and flick the light on and off, on and off, watching to see if it stirred, antagonizing it deeper, making it snappy and angry and full of need.

he relished how the natives feared it, how they’d stack bricks under each bed leg at dusk, raising the beds high to keep it away if it ever escaped in the night. that amused him deep down, a cold amusement. the torment went on like that for months more, until the house-boy finally packed up and moved to another farm far away.

years later he came back and found the child grown into teenage years—no longer the little boy but a broken young man now, right arm gone clean off, face drooping heavy to one side, skin turned yellow, beige like old paper, silent forever, no tongue for words or cheek for smiles, paralysis locking him in.

they’d found him breathless on the floor, cramped up with dizziness and nausea rolling through him, body arched over in agony, writhing slow while his father worked the distant fields and his mother bent over laundry in the back room.

it happened during an argument with the kitchen boy—the jar smashed sudden on the tiles, glass shattering everywhere, and his little friend escaped at last, free into the shadows. only to return that night, crawling back in the dark, silent, to the boy who had tormented it so long.

a sting in its tail,

a slip under the covers,

and an axe to grind.